As far as odd couples go, this is one for the record books.

The ripples in spacetime stirred up by two distant, merging black holes suggest that one of the pair was much bigger than the other. It’s the first definitively mismatched black hole pair spotted by the LIGO and Virgo collaborations, which search for the gravitational waves emitted in the cosmic encounters of black holes. The collision, detected on April 12, 2019, occurred about 2.5 billion light-years from Earth.

For all previous such black hole mergers, the two partners have been of similar size. But in this case, the bigger black hole had a mass about 30 times that of the sun, while the smaller was about eight times the mass of the sun, researchers with the LIGO and Virgo collaborations reported April 18 at a meeting of the American Physical Society, which was held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prior to this result, scientists did not know if such lopsided partnerships existed, or how rare they might be. “This one event represents a big step forward in our understanding,” astrophysicist Maya Fishbach of the University of Chicago said in a talk at the meeting.

[embedded content]

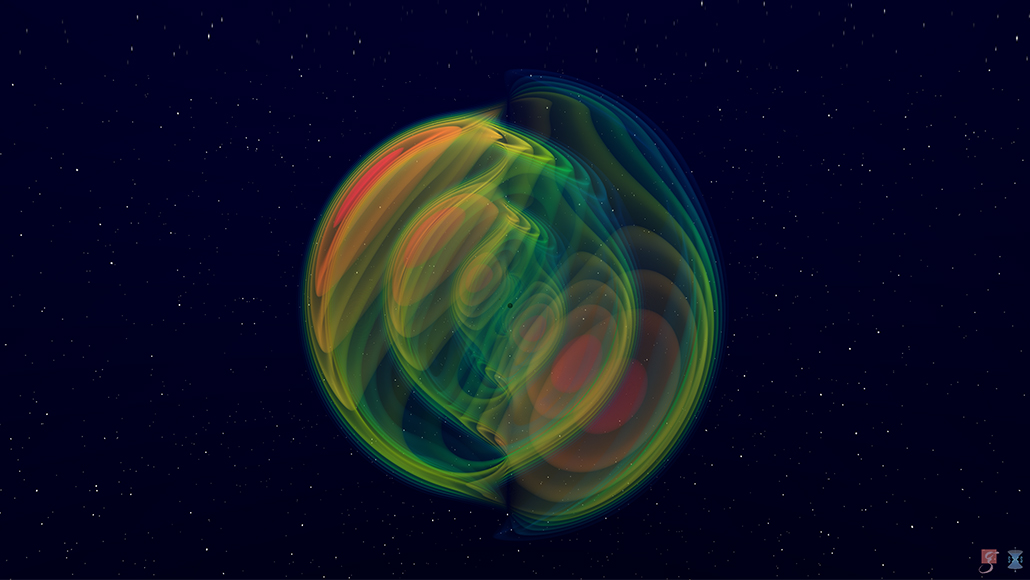

Two black holes, one big and one small, orbit around one another in this simulation, emitting gravitational waves. Blue colors represent weaker gravitational radiation while red is stronger. The undulating line at the bottom traces how the frequency and strength of the waves changes over time. At the finale, the two black holes merge into one. Credits: © N. Fischer, H. Pfeiffer, A. Buonanno (Max-Planck-Institut für Gravitationsphysik), Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes project

Understanding what types of black holes partner up could eventually help answer the question of how the duos form (SN: 6/19/16). The black holes might partner up within a dense star cluster, or when two stars are born together as twins and both collapse into black holes. Both possibilities could occasionally create unequal mass partnerships.

The researchers also tested whether Einstein’s theory of gravity still held up in this new type of black hole collision. Surprise, surprise: Einstein was right again.

The detectors of the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory in the United States and Virgo in Italy are currently shut down, in an early end to operations that was hastened by COVID-19. They’re scheduled to once again start observing the heavens in 2022.

Source: Space & Astronomy - www.sciencenews.org