Wind may be the usual suspect for knocking down trees during hurricanes, but a new survey of forest damage in Puerto Rico after back-to-back hurricanes in 2017 highlights the power of a strong downpour.

When Hurricane Irma passed off the coast of Puerto Rico on September 6, 2017, the storm brought heavy rains but minimal forest damage. Hurricane Maria, which struck two weeks later, was a different story. The strongest hurricane to make direct landfall in Puerto Rico in almost a century, Maria brought wind speeds over 200 kilometers per hour and dropped nearly 1.5 meters of rain in two days on some areas.

Using satellite images and on-the-ground observations at 25 forest plots across the U.S. territory, researchers mapped the devastation wrought by the two storms. An estimated 10.44 million metric tons, or about 23 percent, of Puerto Rico’s total forest biomass was destroyed — but the degree of damage varied by location, researchers report online March 9 in Scientific Reports. Comparing the fraction of forest lost in different places against other local factors, such as wind and rain exposure during the hurricanes, revealed that severe damage was more closely associated with heavy rainfall than strong winds during Maria.

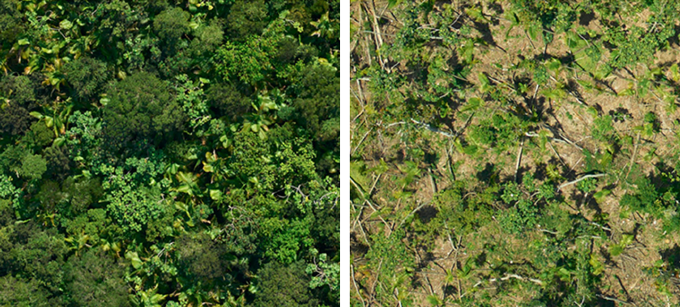

Aerial photographs of El Yunque National Forest in Puerto Rico before (left) and after (right) Hurricane Maria passed in 2017 reveal the damage wrought by this extremely wet, windy tropical storm.M. Uriarte, J. Thompson and J.K. Zimmerman/Nature Communications 2019

Aerial photographs of El Yunque National Forest in Puerto Rico before (left) and after (right) Hurricane Maria passed in 2017 reveal the damage wrought by this extremely wet, windy tropical storm.M. Uriarte, J. Thompson and J.K. Zimmerman/Nature Communications 2019

“It wasn’t something that I was expecting. I thought the big driver would be wind,” says María Uriarte, an ecologist at Columbia University. Hurricane Maria’s rainfall could have played a significant role in toppling trees by pressing down on tree canopies while loosening soil, Uriarte and her colleagues say. Badly damaged areas also tended to be places that were hammered with heavy rains from Irma and had soil that could hold a lot of water. That suggests regions waterlogged by Irma were primed to suffer worse damage from Maria.

The counterintuitive finding that rain played a bigger role than wind in this forest damage suggests that tools for forecasting impacts of tropical storms may need to give more weight to rainfall, says Weimin Xi, an ecologist at Texas A&M University–Kingsville who was not involved in the work. This may be especially important as the warming climate is expected to brew up hurricanes with stronger winds and heavier rains (SN: 9/25/19).

Future super strong hurricanes might have other unexpected consequences for tropical forests. In a study published March 2019 in Nature Communications, Uriarte’s team inspected tree damage in the same forest in northeastern Puerto Rico after Hurricane Hugo, a Category 3 storm as it passed over Puerto Rico in 1989, and again after Maria, nearly a Category 5 storm at that point. Although larger trees with denser wood proved more resistant to breakage during Hugo, as expected, these species were not more resilient during Maria. Rather, more flexible trees, such as palms, were better able to stand their ground against Hurricane Maria without breaking.

If Maria-caliber hurricanes become more common under climate change, this may mean that supposedly sturdy trees, which have fared well during middling hurricanes of the past, may be more vulnerable. That could release more carbon into the atmosphere, as larger felled trees decompose, and shrink the habitats of some species.

Source: Heart - www.sciencenews.org