Three years ago, Kim Cobb was feeling “completely overwhelmed” by the problem of climate change. Cobb spends her days studying climate change as director of the Global Change Program at Georgia Tech in Atlanta, but she felt paralyzed over how to be part of the solution in her personal life. The barriers felt immense.

She decided to start small. On January 1, 2017, she made a personal climate resolution: She would walk her kids to school and bicycle to work two days a week. That change didn’t represent a lot in terms of carbon emissions, she says, “but it was a huge lesson in daily engagement.”

In the beginning, her modest goal seemed daunting, but she quickly discovered that the two simple activities nourished her physical and mental well-being. She wanted to do them every day. “It’s no longer for the carbon — it’s for the fact that I genuinely love riding my bike and walking my kids to school,” she says. And that made her wonder: What other steps was she thinking of as sacrifices that might actually enrich her life?

A November 2019 survey by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication suggests that Cobb isn’t alone in her worries about climate change. Fifty-eight percent of the U.S. residents surveyed were “alarmed” or “concerned” about global warming. Cobb has turned her concern into action. It’s not too late to reduce the damage caused by global warming, but it will take drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, says Jonathan Foley, executive director of Project Drawdown, a San Francisco–based nonprofit research organization that identifies ways to reduce carbon emissions.

To keep global temperatures from rising too quickly, we need to re-engineer our society away from fossil fuels. A 2015 study calculated that to rein in warming, about 80 percent of global reserves of coal, 50 percent of natural gas reserves and 33 percent of the world’s oil must be left unused.

We can’t get to drawdown, the point at which levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere start to steadily decline, with one easy fix, Foley says. Action is required on multiple levels — government, industry and individuals — and across multiple systems, including energy, transportation, housing and food. We need to do all of the things, says Foley, whose organization has identified more than 80 climate “solutions” available now. These range from renewable energy technologies to plant-based diets to mass transit. “To get to drawdown, we need them all,” Foley says.

When it comes to the changes that individuals can make, “the most effective thing that you can do depends on your specific circumstances,” says Christopher Jones, director of the CoolClimate Network at the University of California, Berkeley. His group has produced maps that estimate a household’s carbon footprint based on ZIP code and lifestyle.

The graphics below, based on CoolClimate Network calculations, will help you find your biggest levers for cutting emissions, which for U.S. households are, on average, the equivalent of 48 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year.

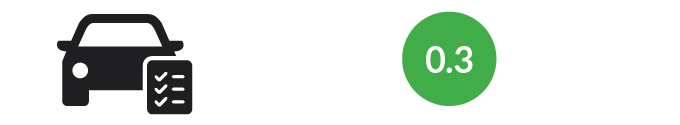

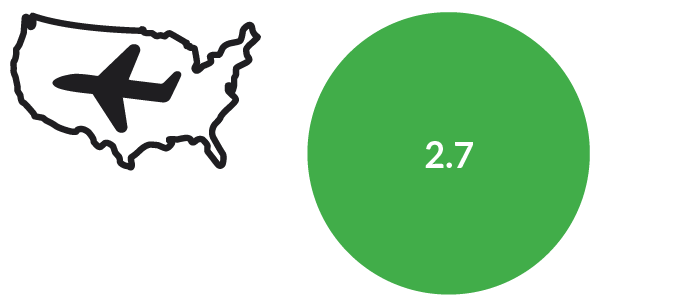

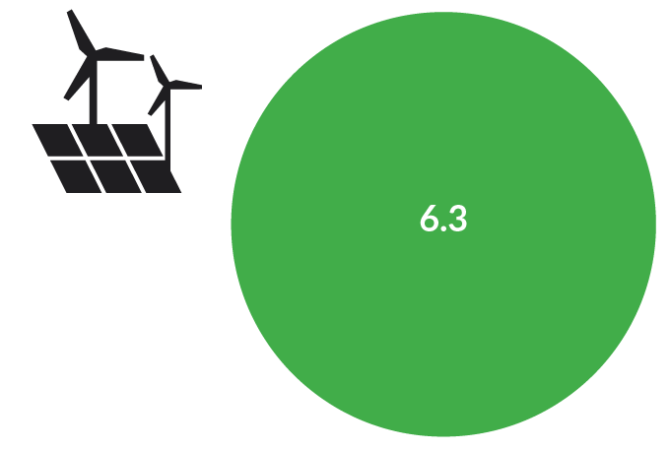

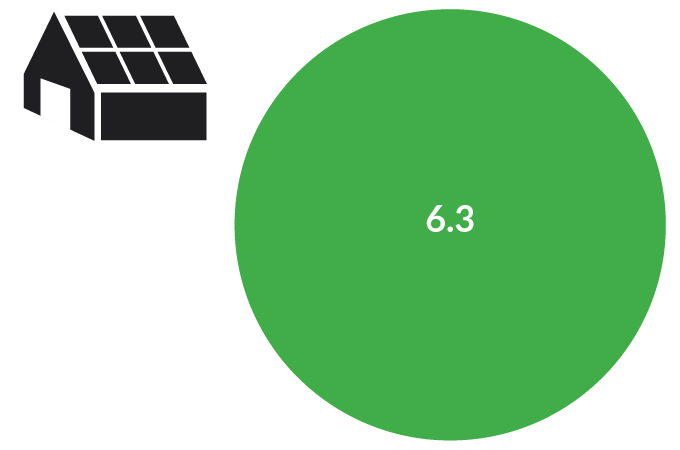

Each action shows the tons of carbon dioxide equivalent saved per year:

Relevant assumptions are shown in italics.

Transportation

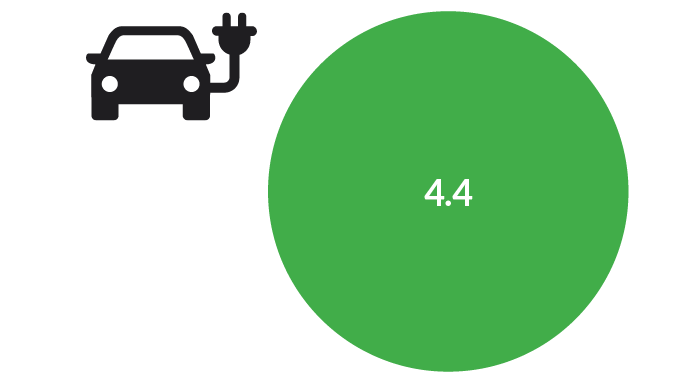

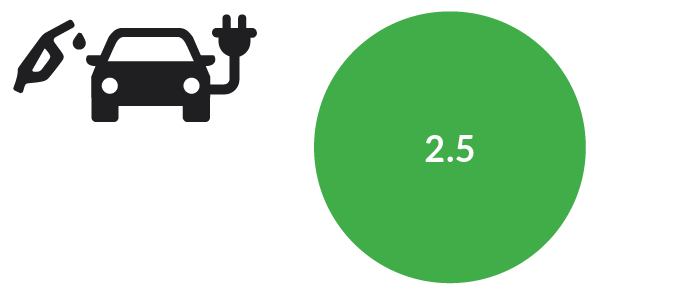

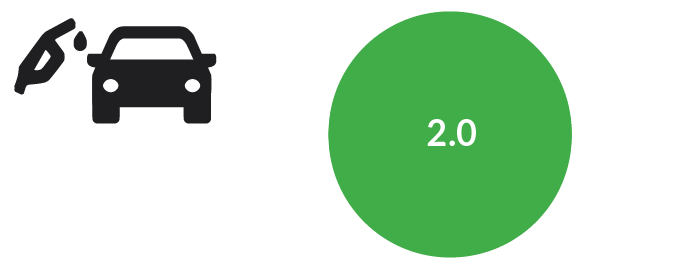

How you get where you’re going is one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions, and the size of your transportation emissions usually depends on where you live, Jones says. City dwellers have more access to public transportation, while people in the suburbs tend to drive a lot more. For people who drive long distances, getting the most fuel-efficient car, a hybrid or an electric, may be the best way to curb emissions. Carpooling when possible, combining trips and leaving the car home once a week also help.

Action: Replace a 25 mpg car with …

An electric car

A hybrid car (55 mpg)

A fuel-efficient car (40 mpg)

Assumption: Driving 12,000 miles per year

Action: Alternate commuting alone in a car with …

Carpooling two days/week

Telecommuting five days/month

Assumptions: Car gets 25 mpg, commute is 25 miles round trip, carpool with one other person

Action: Replace 25 miles of driving per week with …

Bicycling

Assumption: Current car gets 25 mpg

Taking the bus

Assumption: Bus is diesel engine

Action: Practice “eco-driving”

Reduce rapid acceleration and braking and reduce top cruising highway speed from 70 to 65 mph

Assumption: Driving 12,000 miles per year, fuel economy 25 mpg

Action: Change air filters regularly and keep tires properly inflated

These two actions raise efficiency by 3 percent each

If you fly, there’s a good chance that aviation emissions are your biggest lever. Once people can travel again, consider vacationing closer to home and look for alternatives to business travel, such as videoconferencing. Take ground transportation instead of flying whenever possible. When flying can’t be avoided, take the advice of Dan Rutherford, shipping and aviation director at the International Council on Clean Transportation: Fly like a NERD. Choose a New(er) aircraft; book Economy class; take a Regular, medium-sized plane instead of a less-efficient small regional or jumbo jet; and select a Direct flight.

Action: Eliminate one round-trip cross-country flight per year

Assumption: Based on approximate round trip from New York to San Francisco

Shelter

The average U.S. home uses three to four times the electricity of a European one, Foley says. That’s mostly due to inefficient appliances and lighting and insufficient insulation. Those are all things that homeowners can address. Installing solar panels takes a big chunk out of your emissions. But if panels are too costly or just not feasible, purchasing renewable energy from a clean energy provider can offer the same emissions savings. Though options, like installing solar panels, are only available to people who own their home, there are plenty of other things that both renters and owners can do.

Action: Change your source of electricity

Purchase green energy from a clean energy provider

Install solar panels at your home

Assumptions: Household uses 10,700 kilowatt hours of electricity per year and 100 percent of electricity comes from a clean energy provider or from solar panels

If home improvements are in your budget, go for optimized insulation, weather stripping and energy-efficient windows and appliances. Install thermostats that adjust the temperature based on when you’re home and awake. And, of course, bigger houses take more energy to heat, cool and light, plus more space means more stuff. “The majority of emissions regarding shelter come from the stuff you buy,” Jones says. If downsizing is an option for you, it’s worth considering.

Action: Replace 10 incandescent lightbulbs with LEDs

Assumption: Lights are on five hours per day

Action: Reduce your trash output by 20 percent

Assumption: Household throws out 0.5 cubic yards of trash a week

Action: Turn off the lights when not in use

Assumption: Shut five lights at 40 watts each for four hours per day

Action: Turn the thermostat …

Down 5° F in winter

Up 5° F in summer

Assumptions: Home is about 1,850 square feet, heated with electricity

Action: Put desktop computer in sleep mode nights and weekends and turn off monitor during those times

Assumption: Remember to do this 50 percent of the time

Action: Install low-flow showerheads

Assumptions: Household takes two showers per day for eight minutes each; savings comes from heating water.

Action: Plant five trees in your yard

Assumptions: Some of the savings comes from reduced AC use as the result of shade from the trees.

Action: Line dry two loads of laundry per week

Assumptions: Machine-drying four loads of laundry uses 690 kilowatt-hours of electricity

Food

The biggest lever to cut food emissions is to stop producing more food than we need. The United Nations estimates that the annual carbon footprint of global food waste is 4.4 gigatons of CO2 equivalent. Americans, specifically, waste about 25 percent of the food we buy. According to Project Drawdown, adopting a vegetarian diet can also cut emissions, by about 63 percent, while going vegan can reduce them by as much as 70 percent. Agriculture is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, and meat and dairy production are the big contributors. Even cutting back on animal products can make a difference.

Action: Cut five servings a week of …

Beef, pork, lamb

Other (processed meats, nuts …)

Poultry and eggs

Fats, oils, sugar and processed foods

Dairy

Do individual choices matter?

When Cobb looked at her carbon footprint, she found that flying represented about 85 percent of her emissions. So she joined a community of people on Twitter who resolved to fly less, and she committed to cutting her business and personal flights by 30 percent. With the group’s support, she dropped another 30 percent the next year, but it wasn’t always easy. Her pledge didn’t make her many friends within the academic community initially. But the goal of flying less has become more mainstream, at least among her colleagues, as she’s shown it can be done.

“It started as an individual action,” she says, but her decision to forgo certain work travel created new opportunities for virtual conferences and other flying alternatives for her colleagues, too. “It has transformed into a collective-scale action to shift cultural norms,” Cobb says.

Social influence can drive change, says Diana Ivanova, a research fellow at the School of Earth and Environment at University of Leeds in England who reviewed emissions reduction options in April in Environmental Research Letters. If you see other people taking steps to shrink their carbon footprints, “you may feel more empowered to enact changes yourself.”

Researchers call this transmission of ideas and behaviors through a population “behavioral contagion.” That’s where individual action can be a potent force for change, says Robert Frank, a Cornell University economist. “Installing solar panels, buying an electric vehicle or adopting a more climate-friendly diet don’t just increase the likelihood of others taking similar steps, it also deepens one’s sense of identity as a climate advocate,” Frank writes in his 2020 book, Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work. Those actions can also encourage other meaningful actions, like supporting candidates who favor climate-protecting legislation.

Some of the most significant action is happening at state and local levels. Your mayor and city council have a lot of power to reduce the community’s carbon footprint, says Cobb, who found herself getting more involved with each success. She was elected traffic chair of her neighborhood board in 2017 and is now working on improving biking infrastructure to make cycling safer for everyone.

Individual actions can create ripple effects, says ecological economist Julia Steinberger of University of Leeds. Teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg helped spread awareness about aviation emissions, and now overnight train lines between European cities are reopening. “It wasn’t a big industry-wide decision or government regulation. It was a bunch of people deciding, we don’t want to fly anymore,” Steinberger says.

Source: Heart - www.sciencenews.org