Counting universes ought to be easy. By definition, you can stop at 1.

Trouble is, definitions change. A century ago, the “universe” was defined as the Milky Way galaxy. Heretics who disagreed had long been ridiculed— until science staged what became known as the Great Debate, on April 26, 100 years ago. On that date, American astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis articulated opposing views on the scope of the cosmos.

Today astronomers know that the Milky Way, huge as it is, is a mere drop in the cosmic bucket. Just as the sun is only one of 100 billion or so stars swirling within the Milky Way’s pinwheel disk, the Milky Way is only one of hundreds of billions of such galaxies inhabiting a vast, expanding bubble of space.

But in 1920, conventional wisdom dictated that the Milky Way was alone. Most experts insisted that the fuzzy patches of light known as nebulae resided within the Milky Way. Nebulae with a spiral structure might be solar systems in the making, some astronomers suggested.

Others insisted that the nebulae were far, far away, well beyond the Milky Way’s borders. In fact, the heretics argued, the nebulae (at least some) contained stars in quantities comparable to our galaxy, and deserved recognition as “island universes.”

Actually, the island universe idea had been a popular explanation for the nebulae in the mid-19th century. (American astronomer Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel coined the “island universe” label in the 1840s, a translation from a German article referring to the nebulae as Weltinseln.) But by century’s end, the astronomical consensus had affirmed the Milky Way as the sole and rightful universe. Irish astronomer and author Agnes Clerke declared in 1890 that “no competent thinker” believed the nebulae to be galaxies comparable to the Milky Way. She later wrote that the island universe theory had passed into the realm of “discarded and half-forgotten speculations.”

But during the first two decades of the 20th century, new astronomical observations raised doubts. Curtis, for one, maintained that the evidence favored island universes. But Shapley insisted that the nebulae could not be far enough away to be outside the Milky Way. He cited measurements (by Adriaan van Maanen) of motion of the spiral arms within some nebulae; such motion would be undetectable if the nebulae were actually distant galaxies.

In 1919, leaders of the National Academy of Sciences decided it would be fun to hold a debate on the dispute at the academy’s meeting the following April.

Technically, the topic of the debate was to be on “the distance scale of the universe.” On that issue, Curtis was the conservative and Shapley was the heretic. Curtis maintained the more traditional view that the visible Milky Way stretched only about 30,000 light-years across at most, and was possibly much smaller. Shapley thought that the Milky Way had a diameter of 300,000 light-years (much bigger even than today’s estimate of roughly 100,000 light-years or so).

Although Shapley’s view of the Milky Way’s size was radical, it did support the consensus view opposing island universes.

“If, as Shapley maintained, the Galaxy was much larger than had previously been thought, it would be more difficult for Curtis to sustain the claim that the spiral nebulae were independent island universes,” historian Michael Hoskin observed in a 1976 paper analyzing the debate.

As it turned out, the “debate” was nothing that CNN would had televised. Each astronomer just presented a 40-minute talk. Shapley, who went first, read from a typewritten script. Curtis, the better speaker, showed slides, a more powerful way to make his point.

Shapley recounted a potpourri of recent astronomical observations, barely mentioning the island universe theory. He insisted that Curtis’ interpretation of the observations required abandoning “the very foundations of modern astrophysics.” But he acknowledged that if the Milky Way was really small, the island universe idea just maybe could be right.

“If the galactic system is as large as I maintain, the spiral nebulae can hardly be comparable galactic systems,” Shapley declared. “If it is but one-tenth as large, there might be a good opportunity for the hypothesis that our galactic system is a spiral nebula, comparable in size with the other spiral nebulae, all of which would then be ‘island’ universes of stars.”

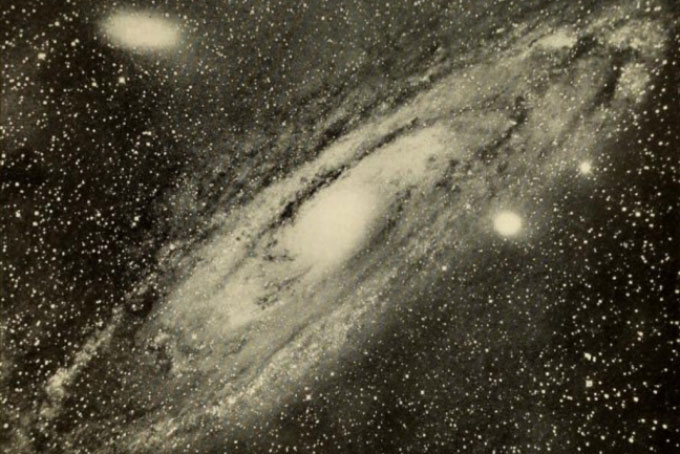

Until 1924, astronomers did not know whether Andromeda (shown in an 1888 image) and other nebulae were a part of the Milky Way or separate “island universes.”From the book Astronomy of To-Day, 1909

Until 1924, astronomers did not know whether Andromeda (shown in an 1888 image) and other nebulae were a part of the Milky Way or separate “island universes.”From the book Astronomy of To-Day, 1909

Curtis presented data supporting his view of a smaller Milky Way, citing various estimates of its diameter ranging from 10,000 light-years to 30,000 light-years. He argued that the analysis of light from spiral nebulae indicated that they were clusters of stars (with similar features to the spectrum of light from the Milky Way itself). “The spectrum of the spiral nebulae offers no difficulties in the island universe theory of the spirals,” Curtis stated. Subsequent slides further built the case for the spirals as island universes.

More detailed arguments (deviating considerably from the original talks) appeared the next year in papers by Shapley and Curtis published jointly under the title “The Scale of the Universe” in the Bulletin of the National Research Council. Resolution of the debate came two years later: Astronomer Edwin Hubble demonstrated that the Andromeda nebula was truly an island universe — full of stars at a distance far exceeding even Shapley’s generous estimate of the Milky Way’s girth.

Faced with new findings, Shapley had to concede. When a letter arrived from Hubble reporting the Andromeda results, Shapley remarked: “Here is the letter that destroyed my universe.”

Shapley had been misled by van Maanen’s measurements — they simply turned out to be wrong. “Shapley … said later that van Maanen was his friend, so of course he believed him,” astronomer Virginia Trimble commented in a 1995 discussion of the debate.

But Shapley had not been entirely defeated. For on another important point, he was right, and Curtis was wrong. In his smaller Milky Way, Curtis placed the sun very near the center, as astronomical consensus dictated. Around the turn of the century, astronomer Simon Newcomb had wondered about that consensus, though, pointing out that ancient astronomers believed with equal confidence that the Earth sat at the center of the universe. Shapley declared that Newcomb was right to be skeptical.

“We have been victimized by the chance position of the sun near the center of a subordinate system, and misled by the consequent phenomena, to think that we are God’s own appointed, right in the thick of things,” Shapley said at the 1920 debate — “in much the same way ancient man was misled, by the rotation of the earth … to believe that even his little planet was the center of the universe.”

Today astronomers all know that Shapley was right about the sun; it is substantially displaced from the galactic center. And everybody knows that Curtis was also right: The Milky Way — home to sun, Earth and humankind — is not a single universe unto itself, but one of a myriad upon myriad of other galaxies — no longer known as island universes, as the definition of “universe” had to be changed.

Source: Space & Astronomy - www.sciencenews.org